Introduction

Databases are never alone. Users, applications, scripts, and even other databases feed information into and extract information from them the way living things consume and distribute environmental -- and each other's -- energy. No database can match Earth's global ecosystem for scale or complexity, but designing and supporting information systems still has more than a few parallels to caring for a smaller one such as a garden, greenhouse, or vivarium.

The classic ecological division can be applied too to the role of a database in an information system: animal, vegetable, or mineral? Identifying which mode is appropriate for a given data model requires understanding, as best possible, the context it inhabits.

"Animal" seems to describe an active organizing principle, embedded (or less kindly, entangled) in operational processes and workflows, adapted, programmed -- in a word, specialized. An "animal" approach does very well in a tightly-focused system or subsystem explicitly built around a single database as the collector of information flows and single source of truth. Lose this focus, and an "animal" database risks becoming more of a giant panda: sluggish, high-maintenance, and a logistical and bureaucratic nightmare.

A more "vegetable" species of database organizes what data it gets and no more, constraining and refining information without taking positive action on it. These databases trade centralization and active control over workflows for adaptability, collecting and organizing information without encoding behaviors and usage assumptions in the more rigid database structure. In systems where the database isn't the only site of information processing or where larger teams and communication structures interact, it can be much easier to work with a less-programmed database treated as a rather than the organizing principle.

Still other "mineral" database designs cede even that minimal authority over information, providing only storage with the bare minimum of structure like the five-thousand-year-old clay tablets onto which the Sumerians stamped everything from ledgers to complaints. It does happen that a situation calls for little more than an

Databases, plural

Every program or system interacting with a database -- not to exclude designers, users, or developers -- also has an ecological role, consuming and generating information, combining it, separating it, adding or eliminating nuance for good or ill. Many of these interacting systems have their own data models, of which part or all of the target system's data model now forms a component (sometimes through the proverbial glass darkly, as anyone who's ever cursed an unexpected VARCHAR(20) can attest).

These connections mean database designs must frequently accommodate at least some of the assumptions, if not elements of the structure, of other data models external to themselves. Information is split: users and bookings in one database, hotel vacancies from another, flight reservations with the airline and duplicated on the users-and-bookings side. Schemas become entangled, and changes in one database have effects on others.

It's always more difficult to manage more things and more interactions between them, and splitting a data model across multiple stores especially has far-reaching consequences. Encapsulating and addressing subsections of a fully relational model is more safely accomplished with schemas, which all major RDBMSs

The most important casualty of splitting a data model is referential integrity. Within a single database, the server can prevent operations which would violate a foreign key constraint, e.g. inserting or updating a record with a nonexistent parent id or

Specialized solutions

Like anything else, referential integrity is a negotiable constraint, and sacrificing it's an option if you get enough in return. Sometimes it isn't even a question being asked, if a data model is simple enough in a graph-theory sense with few entities, few or mostly hierarchical connections between them, or both. Performance and scalability requirements can also make the case for introducing alternatives to the relational model, where some part of a data model represents real information in higher volumes and faster flux than can be accommodated with ease in an RDBMS.

The latter half of the 00s saw a Cambrian explosion of these alternatives. Suddenly there were "NoSQL" databases storing documents, graphs, key-value pairs. Columnar stores achieved shocking performance by turning tables sideways and modeling flat, denormalized data. The newcomers embraced scaling out across networked servers, threw out the ACID playbook in favor of BASE ("Basically Available, Soft state, Eventual consistency"), and developed APIs and domain-specific languages for concepts alien to SQL. Not only that, the reshaping of the conversation around data storage has blurred the boundaries of databases as a concept. Are stream processors like Kafka databases? What about search engines like ElasticSearch? Each fundamentally facilitates the storage and retrieval of information; discussing either requires invoking much of the technical language of databases. More fundamentally, each is a solution to a particular sort of data modeling problem.

| If you need to store and process... | Look towards... |

|---|---|

| Hierarchies with few interconnections, raw structured documents or objects with at least some fields in common | Document databases (Couchbase, MongoDB) |

| Huge volumes of "flat" data such as instrument readings or structured analytics | Column-oriented databases (Cassandra, HBase), time-series databases (TimescaleDB, InfluxDB, Druid) |

| Records identified by a key and queried only by that key | Key-value stores (Redis, LevelDB), caches (memcached) |

| Complex relationships among records with point-to-point navigation | Graph databases (OrientDB, Neo4j, TerminusDB) |

| Transient data feeds in the order of receipt | Stream processors and queues (Kafka, RabbitMQ, ZeroMQ) |

| Files. Lots and lots of files | Cloud file storage (Google Cloud Storage, Amazon S3 and Athena) |

| Unstructured documents, or structured documents with highly variable schemas | Search engines (ElasticSearch, Solr), content repositories (Jackrabbit) |

| Relational data, at planetary scale | NewSQL highly-distributed relational databases (VoltDB, Spanner) |

| At least several of the above | Multi-model databases (FaunaDB, ArangoDB) |

Note the above are examples, not endorsements! Kristof Kovacs also maintains a more detailed summary of many NoSQL options, from the popular to the obscure.

The default

If you don't need to store at least gigabytes worth of exceptions to an otherwise relational data model, you may not even need to leave ACID and referential integrity behind! Relational databases in general are quite capable when it comes to full-text search and storing structured or unstructured documents; PostgreSQL's approach to JSON in particular is extensive, with indexable binary storage and a rich query toolset making hybrid relational-document strategies practical. Both Postgres and other RDBMSs support still other models through server components, extensions, or storage engines, with some specialized stores like TimescaleDB being built on top of relational databases.

So despite the best efforts of dozens of marketing departments, the hoary half-century-old RDBMS remains the go-to general purpose data store, with non-relational solutions finding specialized niches suited to their strengths. NoSQL databases can do all manner of things that their relational counterparts can't, easily or at all, but the relational database is here to stay for the foreseeable future. With server tuning, indexing, and table partitioning, a single relational database can accommodate all but the heaviest workloads. And when even that doesn't suffice, there's still replication.

Replication and architecture

Covering replication techniques in depth falls outside the scope of a guide to data modeling, but their use does invoke consequences that can't be ignored. A replicated database isn't simply bigger: the instant data storage becomes networked, it's no longer a single element of the overall system architecture. Replication introduces a whole new set of concerns surrounding latency, network partitions, maintenance, and more.

The most common form of replication involves writing data only to a single

In an alternative "multi-primary" mode of replication, data can be written to and read from multiple servers, which, networked, are collectively much more resilient under heavy workloads than a single server could ever be. However, working out consensus is complicated, and achieving higher levels of write verification to guarantee durability can be slow. This tends to require simpler data models and more delicate handling of conflicts and rollbacks.

Most NoSQL data stores are designed for clusters, some to the point that being able to run on a single computer at all is almost an afterthought. In particular, NoSQL brought the idea of sharding, or serving partitions of a table from different nodes in the cluster, to the forefront. Sharding is a major factor in the scale these databases achieve, but without replication losing a node still means losing data. Most NoSQL databases offer basic replication, often with automatic failover. A few, like Cassandra and Couchbase, use multiple primaries.

CAP Theorem

His "CAP Theorem" (consistency, availability, partition tolerance: pick two) still resonates today, but, like the animal/vegetable/mineral trichotomy, is an elegant oversimplification -- no more and no less.

Martin Kleppmann described the shortcomings of CAP in detail in 2015, building on an earlier effort by Coda Hale to clarify the "pick two" aspect. Brewer himself has gone on to declare Google's Spanner database "effectively CA", overcoming the AP/CP dichotomy thanks to the sheer scale of Google's network.

Integrating external information

Information rarely circulates between a system's database or databases and its users alone. Most information systems are open systems, with data flowing in from and out to still other information systems. These flows are usually ripe for automation, and at a certain not very large volume it becomes almost obligatory; manual data entry is the last of last resorts. Sometimes external information sources are always-on, with queues, stream processors, or specialized daemons adding records as they arrive but never doing too much at once. Other times, however, realtime data may be unavailable or just plain unnecessary -- monthly sales or yesterday's site analytics don't need to be current to the second.

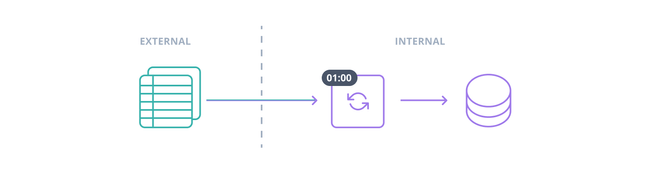

The process of bulk data ingestion is commonly referred to by the acronym ETL, for Extract-Transform-Load, even informally in cases where no extraction or transformation occurs. The archetypal ETL procedure is a cron job or scheduled task which downloads archived data exports, often a flat delimited format like CSV or TSV, from the external system. Records may be transformed by the ETL task as it writes them to the database, or, contravening the acronym, transformed en masse afterwards. Bulk transformation is especially helpful when joins to existing data are involved, since the database can optimize a join for thousands of rows one time much more effectively than it can a single-row join thousands of times.

First-party tooling for data import varies. Proprietary RDBMSs often include specialized ETL management programs, such as SQL Server Integration Services or Oracle Data Integrator, while the major open source and NoSQL options generally stop at basic file loading with applications like mysqlimport and mongoimport, or server-side COPY commands in PostgreSQL and Cassandra (Postgres also offers a client-side \copy instruction in the psql client).

However, third-party ETL automation is becoming a viable business niche, especially as more and more databases are hosted in the cloud. If you've got a lot of different incoming flows or strict regulatory compliance constraints, it can be worth investigating these services. They aren't doing anything you can't with the tools already available to you -- the question is whether you have the time to implement and maintain sufficiently robust ETL processes yourself.

Federation: unified information sources

ETL isn't the only game in town. In 2003, the SQL standard introduced an extension called SQL/MED, for Management of External Data. Files, other databases, other relational or non-relational DBMSs, REST endpoints, directory services -- all these and more involve datasets that look a lot like columns and rows, at least from the right angle. And anything that looks enough like columns and rows can conceivably be queried, if not managed outright, via SQL. The database presents a single face to users and other external systems, while routing requests and changes to the appropriate destination.

After first being implemented by IBM's DB2, it would take several years for any other databases to catch up to SQL/MED. At present, Oracle supports read/write access to flat files as "external tables", while SQL Server can connect to "linked servers", as long as they conform to Microsoft's OLEDB API.

The really interesting things are happening in open source RDBMSs. PostgreSQL introduced foreign data wrappers in version 9.1 and has continued to expand their functionality, and MariaDB's CONNECT storage engine can wrap a plethora of data sources. Moreover, both Postgres' and MariaDB's implementations are extensible: if you have external data in a format no existing wrapper can handle, you can write your own. The Postgres community has even developed a Python framework called Multicorn to simplify the otherwise C-based process of foreign data wrapper development.

The idea of "federated" architectures derives from the dual form of government where regional and central (federal) governments coexist, and like other systems design techniques, its purpose is the management of complexity. Users of the individual subsystems work in and with those subsystems; those concerned only with the operation of the whole interact with the gestalt. In terms of ecological roles, this is very much an "animal" mode of database operation. A federating database is central to the system it inhabits. It draws flows of information to and through itself, makes connections, encodes expectations of subsidiary schemas. But in information ecosystems where such beasts can thrive, SQL/MED is a powerful tool for corralling disparate data sources.

If you want to learn more about what data modeling means in the context of Prisma, visit our conceptual page on data modeling.

You can also learn about the specific data model component of a Prisma schema in the data model section of the Prisma documentation.